香气是葡萄和葡萄酒重要的品质指标,在葡萄果实生长发育过程中,会产生几百种香气物质,包括挥发性醛、醇、酯、酮、萜类和吡嗪类物质等[1],根据它们的合成途径,可分为脂肪酸代谢、氨基酸代谢和异戊二烯代谢产生的香气物质,其中异戊二烯代谢可产生萜烯和降异戊二烯衍生物[2-3]。在葡萄果实中,这些香气物质通常以游离态和糖苷结合态两种形式存在,游离态组分对香气有直接贡献,而没有挥发性的糖苷结合态组分可以在葡萄酒酿造或陈酿过程中水解释放出游离态的苷元,并通过香气组分之间的协同、累加或掩盖等作用,形成丰富而独特的香气[3-5]。降异戊二烯衍生物通常具有苹果、覆盆子、木瓜、紫罗兰等花果香气特征,阈值较低,是葡萄酒香气研究中备受关注的一类香气物质[3,6]。

在葡萄果实中,异戊二烯代谢产生含40碳的类胡萝卜素,后者在类胡萝卜素裂解双加氧酶(carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase,CCD)的作用下,直接生成含有9、10和13个碳的降异戊二烯衍生物,其中含13个碳的C13-降异戊二烯衍生物含量在葡萄果实中最高且受关注最多[3]。除了酶促作用外,在葡萄酒酿造过程中,虽然酿酒酵母并不能产生降异戊二烯,但果实中的类胡萝卜素及其在酶促作用下生成的中间产物可以在酸性条件下非酶促降解产生C13-降异戊二烯衍生物[2,6-9]。研究表明,在葡萄果实中C13-降异戊二烯衍生物的合成积累受到光照、温度、水分等环境因素[10-11]以及摘叶、葡萄整形方式等葡萄栽培措施[12-13]的影响,葡萄酒酿造、陈酿工艺[14]也会影响葡萄酒中这类香气物质含量,对这些影响因素的利用可以有助于实现对葡萄酒中C13-降异戊二烯衍生物含量的精准调控。

近年来,对于葡萄和葡萄酒中C13-降异戊二烯衍生物种类和含量鉴定、合成途径、影响因素等研究较多,随着各种组学技术的发展和数据的整合分析,极大地促进了对C13-降异戊二烯衍生物合成及调控机制的理解。笔者综述了葡萄果实及葡萄酒C13-降异戊二烯衍生物合成机制以及在果实发育、葡萄酒酿造过程影响因素的研究进展,以期为寻找有效的调控措施改善葡萄和葡萄酒中C13-降异戊二烯衍生物含量、提高葡萄与葡萄酒香气质量提供参考。

1 葡萄与葡萄酒中C13-降异戊二烯衍生物的种类及其香气贡献

类胡萝卜素具有高度共轭的双键结构,极不稳定,在葡萄果实和葡萄酒中经过化学和酶促作用产生保留末端基团、具有羰基结构的C13、C11、C10和C9降异戊二烯衍生物[6]。在葡萄酒中已鉴定的降异戊二烯衍生物有β-大马士酮[2-Buten-1-one,1-(2,6,6-trimethyl-1,3-cyclohexadien-1-yl)-]、β-紫罗兰酮[3-Buten-2-one,4-(2,6,6-trimethyl-1-cyclohexen-1-yl)-]、三甲基二氢萘(1,1,6-Trimethyl-1,2-dihydronaphthalene,TDN)、葡萄螺烷(1-Oxaspiro[4.5]dec-7-ene,2,10,10-trimethyl-6-methylene-)、猕猴桃醇(actinidol)、雷司令缩醛(2,2,6,8-tetramethyl-7,11-dioxatricyclo[6.2.1.0(1,6)]undec-4-ene)、(E)-1-(2,3,6-三甲基苯)-1,3-丁二烯[(E)-1-(2,3,6-trimethylphenyl)buta-1,3-diene;TPB]、环柠檬醛(β-Cyclocitral)、三甲基环己酮(2,2,6- Trimethylcyclohexanone;TCH)、6-甲基-5-庚烯-2-酮(6-Methyl-5-hepten-2-one)等[3,6]。在葡萄果实中,C13-降异戊二烯衍生物种类最多,包括β-大马士酮、β-紫罗兰酮、α-紫罗兰酮[3-Buten-2-one,4-(2,6,6-trimethyl-2-cyclohexen-1-yl)-]、香叶基丙酮(5,9-Undecadien-2-one,6,10-dimethyl-)、TDN 等[3],具有丰富的花果香气如热带水果、紫罗兰、覆盆子等香气特征[6,12,14],是葡萄酒,尤其是非芳香型葡萄酒中最重要的果实来源香气成分之一。C13-降异戊二烯衍生物的香气作用受到浓度和阈值的影响,TDN 质量浓度为10~30 µg·L-1,使‘霞多丽’(Vitis vinifera‘Chardonnay’)葡萄酒具有典型的‘雷司令’(V.vinifera‘Riesling’)葡萄酒的特征,低于10µg·L-1,葡萄酒的果味被掩蔽,而高于30µg·L-1,则出现煤油的异味[15]。在葡萄酒中游离态C13-降异戊二烯衍生物虽然含量较低,但通常高于其感官阈值,直接对香气产生贡献,另外,在葡萄果实中部分C13-降异戊二烯衍生物以亲水、无味的糖苷结合形式储存,这些非挥发性的前体物质是潜在的香气作用物,在发酵和陈酿过程中通过酸解或酶解,释放游离态C13-降异戊二烯衍生物,增强葡萄酒香气[16]。

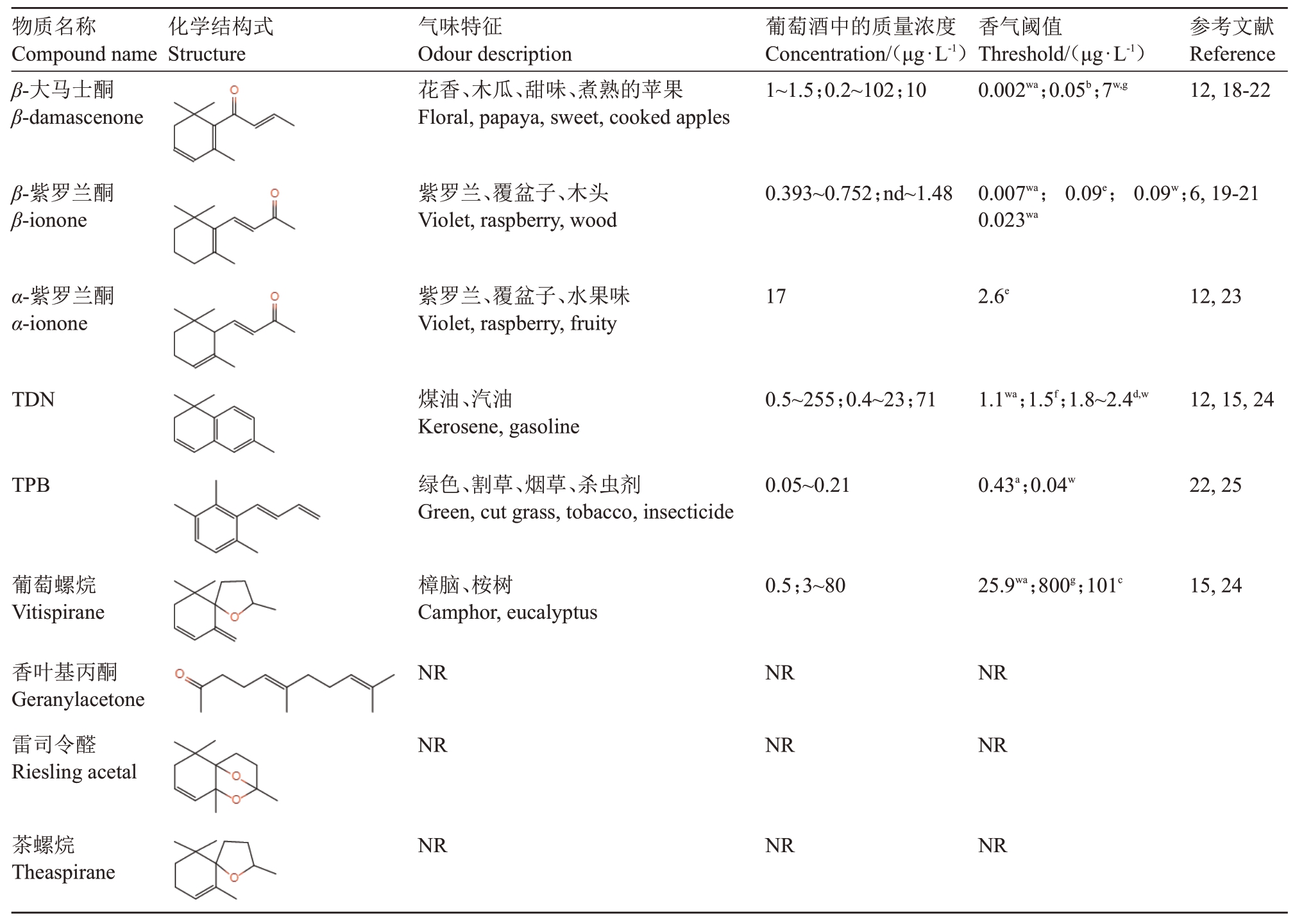

受到许多因素如葡萄品种、酒龄、检测方法、检测人群的影响,C13-降异戊二烯衍生物在葡萄酒中的含量和阈值有较大差异(表1)。葡萄酒中,‘雷司令’TDN的含量明显高于‘赤霞珠’(V.vinifera‘Cabernet Sauvignon’)、‘霞多丽’、‘美乐’(V. vinifera‘Merlot’)等其他品种[17]。受到基质的影响,阈值也显示出一定的差异,与在水中相比,酒精的存在使TDN的检测阈值提高;不同的感官测定方法也使测得的阈值存在差异,相对于受过培训的专家而言,普通消费者测得的阈值往往偏高[15,17]。气味活性值(odor activity value,OAV)常被用于粗略地评估香气化合物对葡萄酒的感官贡献,它指香气化合物浓度与其感觉阈值之比,当OAV 等于或大于1 时,被认为该香气物质对葡萄酒有直接的感官贡献。如上所述,香气阈值受其所处的基质体系的强烈影响,因此,在计算香气化合物OAV时,需要说明香气阈值的来源。

表1 葡萄酒中C13-降异戊二烯衍生物的种类、结构、浓度及感觉阈值

Table 1 Types,structure,concentrations and sensory threshold of C13-norisoprenoids in wine

注:wa.水;w. 葡萄酒;a.10%(φ)乙醇水溶液;b.10%~12%(φ)乙醇水溶液;c.酒精浓度为12%;d. 酒精浓度为8%~14%;e.模拟酒溶液(11%酒精,7 g·L-1 甘油,5 g·L-1 酒石酸,pH 3.4);f.12%酒精,可滴定酸10 g·L-1,pH 3.0;g.差别阈值;NR.未报告;nd.未检出。

Note:wa.water;w.wines;a.10%(φ)alcohol;b.10%-12%(φ)alcohol;c.12%alcohol;d.8%-14%alcohol;e.Imitated wines(11%alcohol,7 g·L-1 glycerin,5 g·L-1 tartaric acid,pH 3.4);f.12%alcohol,10 g·L-1 titratable acid,pH 3.0;g.Differential threshold;NR.Not reported;nd.Not detected.

?

C13-降异戊二烯衍生物除了本身的香气特征外,可以通过与葡萄酒中其他香气物质互作,增加其他组分的气味,例如,β-大马士酮可以降低肉桂酸乙酯和己酸乙酯感觉阈值,增强果香[4];在脱香葡萄酒中,添加少量β-大马士酮和β-紫罗兰酮可以提高酯类混合物的果香[26]。C13-降异戊二烯衍生物也具有减弱气味的作用,β-大马士酮能够提高异丁基甲氧基吡嗪(2-isobutyl-3-methoxy pyrazine,简称IBMP)的阈值,减弱葡萄酒中的青椒气味[4]。由此可见,单纯用OAV来评判香气化合物对葡萄酒香气的贡献有较大局限性,未来研究将关注C13-降异戊二烯衍生物与更多种类的香气物质的相互作用及其对感官的影响。

2 葡萄果实中C13-降异戊二烯衍生物的积累与调控

2.1 果实发育过程中C13-降异戊二烯衍生物的积累规律

在葡萄果实发育过程,C13-降异戊二烯衍生物从转色前开始积累,持续到转色后一段时间[27],之后其含量的变化规律在不同研究中有所不同,Asproudi等[28]研究发现,在‘内比奥罗’(V. vinifera‘Nebbiolo’)葡萄果实成熟前一段时间,C13-降异戊二烯衍生物积累速度减缓。‘西拉’(V.vinifera‘Syrah’)和‘赤霞珠’葡萄果实在转色前到转色结束后2周,总降异戊二烯含量持续增加,随后略有下降,采收前2周含量再次增加,整体上随着果实成熟,总降异戊二烯含量呈现上升趋势[23]。Zhang等[29]也观察到,‘西拉’果实在转色前β-紫罗兰酮、(E)-β-大马士酮、茶螺烷含量达到峰值,之后基本保持稳定,在达到商业采收前2 周C13-降异戊二烯衍生物总量缓慢下降。研究认为,果实成熟时C13-降异戊二烯衍生物含量的下降可能与转色期到成熟期之间糖苷结合态的积累有关[7],随着葡萄果实进一步成熟,大多数C13-降异戊二烯衍生物含量都呈现降低趋势[30],与24%~28%时采收相比,23%时采收的葡萄果实中β-大马士酮、β-紫罗兰酮、TDN、TPB含量均较高[31]。另一项研究也表明,早采的‘赤霞珠’果实中β-大马士酮含量更高[32]。在葡萄酒中的研究也印证了这一点,相对于达到成熟采收标准的果实酿造的葡萄酒,提前1~2周采收的葡萄酿造的葡萄酒中β-大马士酮、β-紫罗兰酮、α-紫罗兰酮含量更高[14]。但也有相反的研究报道指出,随着果实成熟度提高,C13-降异戊二烯衍生物含量有所增加,推测可能是由于果实部分脱水所致[22]。不同的C13-降异戊二烯衍生物在果实中的变化规律也不尽相同,转色前β-大马士酮、葡萄螺烷和TDN总量持续增加,而α-紫罗兰酮和β-紫罗兰酮总含量缓慢下降[7]。

葡萄发育和成熟过程中降异戊二烯衍生物的积累规律,可能会受到研究中取样时间点及取样个数的影响,取样点个数过少,则难以确定在两个时间点之间及之外C13-降异戊二烯衍生物的变化情况[30]。因此,在研究葡萄果实发育过程中C13-降异戊二烯香气物质的积累规律时,应该精细采样,尽可能缩短田间取样间隔时间。

2.2 C13-降异戊二烯衍生物的合成机制

葡萄中C13-降异戊二烯衍生物的生物合成与调控已有一些综述报道[3],它主要是通过含40 个碳的类胡萝卜素裂解、氧化产生的,简言之,植物经过质体中的甲羟戊酸(mevalonate pathway,简称MEP)途径生成异戊二烯焦磷酸(IPP)和二甲基烯丙基焦磷酸(DMAPP),二者进一步生成牻牛儿基牻牛儿基焦磷酸(GGPP),然后在八氢番茄红素合成酶(phytoene synthase,PSY)等作用下产生番茄红素,在番茄红素ε-环化酶(lycopene ε-cyclase,LCYe)和番茄红素β-环化酶(lycopene β-cyclase,LCYb)作用下产生α-胡萝卜素和β-胡萝卜素,进一步反应生成其他种类的类胡萝卜素[33],例如,β-胡萝卜素、叶黄素、新黄质、玉米黄质、紫黄质等[24],在CCD酶作用下生成降异戊二烯。类胡萝卜素与不同的C13-降异戊二烯衍生物含量之间有一定对应关系,研究发现,葡萄果实发育过程中β-大马士酮与类胡萝卜素含量之间存在负相关,α-紫罗兰酮、β-紫罗兰酮与大部分类胡萝卜素含量之间呈正相关,葡萄螺烷与新黄质含量呈正相关[7]。

在葡萄中发现并鉴定了3个与类胡萝卜素降解产生C13-类异戊二烯衍生物有关的VvCCD 基因,即VvCCD1、VvCCD4a、VvCCD4b。其中,VvCCD4a 主要在叶片和成熟果实中表达,VvCCD4b则主要在果实中表达,在‘赤霞珠’果实中VvCCD4b表达与β-大马士酮、β-紫罗兰酮和香叶基丙酮积累呈显著正相关,VvCCD4b 被看作是C13-降异戊二烯合成积累的关键酶。VvCCD1 自绿果期表达量开始增加,在转色期达到峰值,随后表达量下降,而VvCCD4a 和VvCCD4b则在整个绿果期和转色期表达量都较低,成熟时表达量明显上升[33-35]。这3 个CCD 均能够催化环状和链状类胡萝卜素,生成C13脱辅基类胡萝卜素产物[9],利用酿酒酵母过表达VvCCD1 或VvCCD4b,证明了VvCCD1 和VvCCD4b 可以使β-胡萝卜素在9,10(9’,10’)位置发生裂解生成β-紫罗兰酮,在7,8(7’,8’)位置裂解生成β-环柠檬醛[8]。还有一种由β-胡萝卜素生成β-紫罗兰酮的可能机制是:β-胡萝卜素在CCD的作用下在9’,10’位置发生裂解产生β-紫罗兰酮和一个27 碳醇10’-脱辅基-β-胡萝卜素-10’-醇,后者在9,10 位继续裂解产生第二个β-紫罗兰酮[6]。

在多数情况下,葡萄果实中C13-降异戊二烯衍生物与类胡萝卜素含量之间表现出复杂的相关性,这似乎说明了有些C13-降异戊二烯组分并非是类胡萝卜素的直接酶解产物,可能是化学酸解作用产生的[7],例如,玉米黄质和紫黄质可以在VvCCD1作用下分别生成3-羟基-β-紫罗兰酮和3-羟基-5,6-环氧-β-紫罗兰酮,后者经进一步化学反应产生β-紫罗兰酮[27];新黄质在CCD 作用下生成蚱蜢酮(grasshopper ketone)和巨豆-6,7-二烯-3,5,9-三醇(megastigma-6,7-dien-3,5,9-triol),随后进一步酶解和糖基化,最后通过酸解作用产生β-大马士酮[13]。另有研究认为,β-大马士酮可能通过中间产物丙二烯三醇转化生成二醇最终生成[36]。β-大马士酮本身也被认为可能作为其他C13-降异戊二烯衍生物的前体物质存在[7]。

3 影响葡萄果实中C13-降异戊二烯衍生物合成积累的因素

3.1 气候

光照、水分、温度等气候因素都会影响葡萄果实香气物质的合成。有研究表明,葡萄果实中(E)-β-大马士酮和β-紫罗兰酮的积累受温度、湿度、日照时长、无霜天数等的强烈影响[37];不同年份间气候的差异可能是造成葡萄酒中香气差异的重要原因,降雨量较多、气候较炎热的年份酿造的葡萄酒中降异戊二烯衍生物含量较高[38]。气候会影响前体物质类胡萝卜素的生成,气候较凉爽、光照相对较弱有利于类胡萝卜素的积累,相反,温度较高阳光较充足的葡萄园生长的果实中C13-降异戊二烯衍生物含量较高[39]。在生产实践中,增加光照能够提高葡萄果实中C13-降异戊二烯衍生物含量,全年光照累计辐射总量高的年份β-紫罗兰酮和β-环柠檬醛含量更高[13]。降低光照不利于C13-降异戊二烯衍生物的积累,与遮阴的葡萄相比,光照下的葡萄果实中TDN、葡萄螺烷、TPB 等物质的浓度更高[40-41]。另外,使用聚脂薄膜降低葡萄果穗附近紫外线强度,一定程度上降低了β-大马士酮、β-紫罗兰酮、顺式茶螺烷等C13-降异戊二烯衍生物含量[42]。

温度是影响酿酒葡萄生理的关键因素,它通过影响葡萄的生长周期对C13-降异戊二烯衍生物具有调节作用[43]。研究发现,在气温较高的条件下,葡萄酒中β-大马士酮、β-紫罗兰酮、α-紫罗兰酮含量更高[44]。温暖而非炎热的气候有利于TDN的生成,相对于气候凉爽的地区,温暖且日照时间较长地区生产的葡萄酒中TDN 浓度更高[10,45]。同样地,与气候温暖的新疆五家渠和宁夏玉泉营地区相比,气候相对炎热的山东烟台和陕西泾阳地区‘赤霞珠’果实中降异戊二烯类物质含量较高[37]。

另外,干旱对C13-降异戊二烯衍生物积累有积极作用,相对于河北昌黎地区夏季的高温多雨,甘肃高台地区干燥气候增加了葡萄果实中香叶基丙酮和(E)-β-大马士酮含量[34,46]。

3.2 栽培措施

既然环境条件能够影响葡萄果实香气物质含量,在农业栽培中,可以通过调节葡萄园或果际水分、温度、光照等因素,调控葡萄果实中C13-降异戊二烯衍生物的合成积累[47]。

3.2.1 调亏灌溉 适量水分胁迫会促进葡萄次生代谢产物的生成,葡萄果实中的C13-降异戊二烯衍生物含量随着植株缺水程度的增加而增加[11]。在需要灌溉的地区,调亏灌溉提高了β-大马士酮含量[32]。与完全灌溉相比,减少灌溉量可以增加葡萄中某些C13-降异戊二烯衍生物及其前体物质含量[48],类似地,相对于两侧灌溉,葡萄藤单侧交替灌溉可提高果实中β-大马士酮,β-紫罗兰酮和TDN含量[49]。

3.2.2 摘叶 葡萄果穗周围的微气候影响挥发性物质的成分[47],通过摘除冠层和侧枝的叶片增强果穗曝光,可增加果实C13-降异戊二烯衍生物含量,同时类胡萝卜素含量也有所提高[50]。在美国俄勒冈州维拉米特河谷凉爽气候条件下,对葡萄果穗附近叶片进行摘除,有效地增加了β-大马士酮等C13-降异戊二烯衍生物及其前体物质含量[51]。类似地,在南非埃尔金产区对葡萄进行摘叶处理,使果穗曝光,相对于未摘叶组,降异戊二烯类物质尤其是香叶基丙酮含量明显增加[52]。Wang 等[53]利用Meta 分析总结发现,大多数研究表明,果际摘叶处理显著提升β-大马士酮含量,转色期前摘叶效果更明显,较高的摘叶程度会产生更多的β-大马士酮。然而,有一些研究却发现,增加光照对葡萄果实C13-降异戊二烯衍生物含量没有影响[23],在克罗地亚伊斯特拉产区进行葡萄摘叶处理,β-大马士酮含量并没有明显变化[54]。除此以外,增强光照在某些情况下反而不利于C13-降异戊二烯衍生物的积累,在我国新疆产区强光干热的大陆性气候条件下生长的‘赤霞珠’果实中,(E)-β-大马士酮和β-紫罗兰酮含量与生长季的日照时长存在负相关关系[37],摘叶所引起果穗曝光导致了葡萄果实中C13-降异戊二烯衍生物积累减少[55]。这些结果说明了摘叶处理在气候相对凉爽地区能够显著增加C13-降异戊二烯衍生物含量,而在强光干热地区则出现相反效果,甚至可能会引起果实灼伤[56]。

总而言之,通过摘叶处理,可以调节葡萄果实中C13-降异戊二烯衍生物含量,但其效果受到葡萄品种、种植地气候条件[55-56]、摘叶时间[57]、摘叶部位(冠层、果际)[50]、摘叶程度[53]等许多因素的影响。

3.2.3 整形方式 树体整形方式可以调节葡萄生长的微气候,改变果实品质,不同架形的葡萄树生长的果实中C13-降异戊二烯衍生物含量有所差异[40]。比较葡萄新枝垂直分布形(vertical shoot-positioned)、日内瓦双帘式(Geneva double curtain)、斯马特-戴森式(Smart-Dyson)3 种葡萄树体整形方式下的果实,其β-大马士酮积累存在较大的差异,在斯马特-戴森式整形中β-大马士酮含量最高[58]。另一研究比较了5种不同整形方式对葡萄酒挥发性物质的影响,C13-降异戊二烯衍生物总量在斯科特-亨利式(Scott-Henry)整形方式中最高,在新枝垂直分布形中最低,而大马士酮含量则在日内瓦双帘式中最高[40]。

3.2.4 其他栽培措施 避雨栽培可以改变葡萄周围的温度、光照、水分等条件,降低降异戊二烯类物质的合成[59];He 等[60]研究表明,与露天栽培相比,避雨栽培条件下生长的葡萄所酿的葡萄酒中β-大马士酮含量明显降低。但在迟明等[61]的研究中,避雨栽培和常规栽培模式种植的葡萄果实中降异戊二烯类物质含量无明显差异。

研究表明,葡萄园行间生草有许多功能,在夏季降雨或有灌溉的地区,行间植物与葡萄进行水的竞争,减弱水消耗对营养生长的阻碍,同时降低冠层密度、增加果穗暴露,有利于提高葡萄品质;葡萄园行间种植苜蓿增加了葡萄中β-大马士酮和α-紫罗兰酮含量[62]。

此外,疏穗处理可以改善葡萄树体的库源平衡,明显提高葡萄果实中β-大马士酮含量[63]。有研究认为,疏穗处理增加了树体的叶果比,为光合作用提供有利条件,有利于前体物类胡萝卜素的积累,从而提高了果实中β-大马士酮和β-紫罗兰酮含量[64]。

砧木不同也会导致葡萄果实中降异戊二烯积累产生差异[17],在8 种砧木对‘赤霞珠’果实香气物质影响的研究中发现,砧木101-14(河岸葡萄V.riparia×沙地葡萄V.rupestris),Ganzin 1(欧洲葡萄V.vinifera×沙地葡萄V. rupestris),110R(冬葡萄V.berlandieri×沙地葡萄V. rupestris)和5BB(冬葡萄V.berlandieri×河岸葡萄V.riparia)嫁接的‘赤霞珠’成熟果实中,C13-降异戊二烯衍生物含量相对较高[65]。当然,砧木的影响可能与葡萄树体的生态适应性有关,其影响降异戊二烯香气物质积累的机制尚不明确。

3.3 植物生长调节剂的应用

调控葡萄果实品质的另一种方法是应用植物生长调节剂,如赤霉素(GA3)、萘乙酸(NAA)等,通过诱导次生代谢改变C13-降异戊二烯衍生物含量。向葡萄花序喷施GA3溶液,可以提高果实中C13-降异戊二烯衍生物含量,虽然在两年间最佳的GA3浓度并不相同,但GA3处理明显提高了结合态β-大马士酮、TDN、葡萄螺烷和茶螺烷含量[66]。而对于脱落酸(ABA),效果则不相同,外源ABA 虽然能够加速果实的成熟进程,但并没有影响葡萄果实中C13-降异戊二烯衍生物浓度[41,67]。成熟前80 d 左右向葡萄果穗喷施氯吡苯脲(CPPU),可明显上调VvCCD 的表达,促进类胡萝卜素的降解,有利于C13-降异戊二烯衍生物的积累[68]。转色期前在葡萄果实表面喷施NAA,延缓了果实成熟进程,促进了转色和成熟阶段果实中VviCCD4a 和VviCCD4b 的表达,提高了C13-降异戊二烯衍生物含量[67]。

除了常见的植物生长调节剂外,一些新型植物生长调节剂如酵母提取剂的使用,也会影响葡萄中二氢-β-紫罗兰酮、(Z)-β-大马士酮、(E)-β-大马士酮和β-紫罗兰酮含量[69]。葡萄藤应用茉莉酸甲酯、苯并噻二唑都可以增加C13-降异戊二烯衍生物含量[70]。不同的是,对葡萄叶面和侧枝喷施茉莉酸甲酯和壳聚糖溶液,也会使葡萄和葡萄酒中C13-降异戊二烯衍生物总量降低[69,71]。

迄今,关于气候因子、栽培措施和植物生长调节剂对葡萄果实中C13-降异戊二烯衍生物物含量的影响已经有许多研究报道,但多数研究仅停留在对现象的描述,关于其影响机制深入剖析的研究仍然很少。

4 葡萄酒中C13-降异戊二烯衍生物的产生及影响因素

C13-降异戊二烯衍生物是葡萄酒中重要的品种香气[18],葡萄酒中,这类香气物质一方面来自于葡萄原料的直接浸出,另一方面,来自于果实中浸出的前体物的新合成。

4.1 葡萄酒中C13-降异戊二烯衍生物的合成

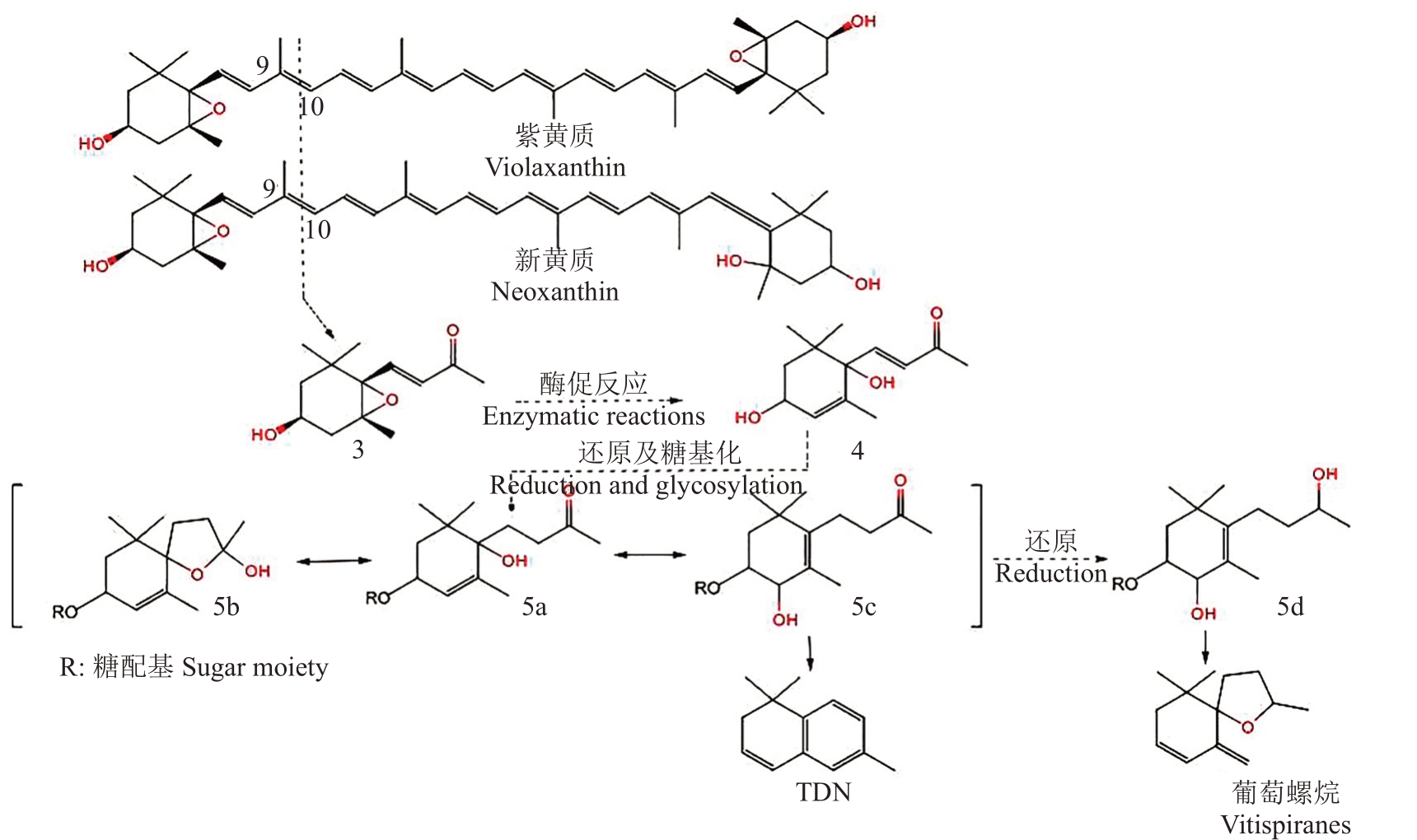

葡萄酒中许多C13-降异戊二烯衍生物含量都高于葡萄果实中,说明葡萄酒中存在化学转化产生C13-降异戊二烯衍生物的可能性[36]。在葡萄酒发酵过程中,酶水解或酸水解糖苷结合态香气物质,可以得到游离态β-大马士酮、β-紫罗兰酮、葡萄螺烷、雷司令缩醛、TDN 等[72]。在年轻葡萄酒中,TDN 含量通常较低,但在陈年葡萄酒中浓度增加,推测TDN的增加主要是由于酸不稳定的糖苷态类胡萝卜素代谢物的水解和重排生成的[73],新黄质和紫黄质最可能是TDN合成的原始类胡萝卜素,其通过酶解反应生成图1 中物质4,经物质4 后续转化产生TDN,虽然这种机制并不确定,但物质4 的还原形式物质5a及烯丙基重排异构体5c 已在‘雷司令’酒中确定为TDN 的前体物质[73]。TDN 与葡萄螺烷之间也存在显著的相关关系,可能具有相同的代谢途径[7],通过TDN生成途径物质5c中C9酮的还原,可得到葡萄螺烷的前体物质,如图1所示[73]。除了TDN,关于β-紫罗兰酮和β-大马士酮的非酶促合成也有一些报道,但这些报道主要是通过体外实验得到的,未见体内证据相验证,这里并不做阐述。

图1 TDN 和葡萄螺烷合成的假设机制[73]

Fig.1 Postulated mechanism of formation of TDN and vitispiranes[73]

4.2 影响葡萄酒中C13-降异戊二烯衍生物含量的因素

4.2.1 葡萄果实大小 酿酒葡萄果实的直径在单个葡萄园,葡萄植株和单个葡萄果穗中变化很大,香气物质主要存在于果皮中,果实大小会影响到果皮与果肉的比例,从而导致葡萄酒香气成分的差异[74];果实皮肉比增大,利于更多果皮中的香气成分进入到葡萄酒中。研究发现,利用体积较小的葡萄果实酿造的葡萄酒中降异戊二烯类物质含量更高[75]。在大、中、小三种大小的葡萄果实中,中等大小的‘赤霞珠’和‘美乐’果实中β-大马士酮、β-紫罗兰酮和6-甲基-5-庚烯-2-酮含量较高[76]。根据这些结果,似乎中等偏小的葡萄果实中C13-降异戊二烯衍生物的含量较高。但也有不一致的结论,在Ziegler 等[24]的研究中,浆果大小对葡萄酒中TDN和葡萄螺烷的形成没有影响。吴明辉等[77]也发现,浆果大小与β-大马士酮含量之间没有明显关系。

4.2.2 发酵工艺 发酵工艺对葡萄酒中C13-降异戊二烯衍生物含量的影响主要有以下几个方面:

(1)原料前处理:果实采后处理会引起葡萄酒中C13-降异戊二烯衍生物含量的变化。在冰酒的酿造中,葡萄果实原料是经过反复冻融和脱水的,相对于干型葡萄酒,冰酒中(E)-β-大马士酮的稀释因子更高[78],延迟采收皱缩脱水的果实相对于饱满果实酿造的葡萄酒,β-大马士酮含量更高[79];葡萄进行采后脱水处理后降异戊二烯类物质种类减少,但利用失水20%和30%的果实酿造葡萄酒,β-大马士酮和3-氧代-紫罗兰醇含量有所提高[80]。这些可能都是由于果实失水产生的浓缩效应导致的。不过,‘北冰红’葡萄果实在经过脱水处理后茶螺烷和结合态β-大马士酮含量却降低,游离态β-大马士酮含量升高[81];也有报道指出,对采后葡萄果实或果汁进行冷冻处理也能够影响其中C13-降异戊二烯衍生物含量[82]。

酿造工艺会影响葡萄酒中C13-降异戊二烯衍生物含量,酿造前对已压碎的浆果进行50℃处理会提高葡萄酒中β-大马士酮含量[83],这可能是因为高温有利用果皮成分的浸出。碳浸渍技术对葡萄酒颜色和香气有积极作用,如增加乙酯类物质增加果香[84],但浸渍对C13-降异戊二烯衍生物影响的报道较少,在一项研究中,相对于传统酿造方法,碳浸渍工艺使葡萄酒中β-大马士酮含量降低[85]。

(2)发酵容器:酿造容器差异也会影响葡萄酒中C13-降异戊二烯衍生物,进行同样的发酵处理,利用自动泵送罐发酵后葡萄酒β-大马士酮含量提高,而在自动打孔罐中发酵葡萄酒β-大马士酮含量降低[86]。

(3)酵母菌株:有研究表明,酿酒过程中添加不饱和脂肪酸,可能会通过改善发酵环境对酵母细胞膜造成的损害,增加酵母生物量并增强发酵活性,进而增加香气物质的积累[87],虽然目前添加不同种类和不同量不饱和脂肪酸出现的结果并不一致,但添加一定浓度的油酸、亚油酸和α-亚麻酸增加了β-大马士酮含量[88]。

非酿酒酵母具有较高的糖苷酶活性,其糖苷酶对酿酒条件如高糖、乙醇、低pH、低温有更高的耐受性,且相对于酿酒酵母特异性更强,在发酵初期可以促进C13-降异戊二烯衍生物的释放,与AR2000糖苷酶相比,有孢汉逊酵母(Hanseniaspora uvarum)中的糖苷酶更有效地催化了糖苷态C13-降异戊二烯衍生物的水解,避免其他不良风味物质的释放[89]。云假丝酵母(Candida humilis)与酿酒酵母(Saccharomyces cerevisiae)的混合发酵与单一发酵相比明显提高了β-大马士酮含量[90]。类似的,与单纯的酿酒酵母发酵相比,使用仙人掌有孢汉逊酵母(Hanseniaspora opuntiae)与商业酿酒酵母DV10混合发酵使冰酒中β-大马士酮含量提高8.85%[91]。

除了混合发酵与单一发酵的区别外,不同非酿酒酵母的添加对C13-降异戊二烯衍生物的影响也不相同,利用克鲁维酵母(Pichia kluyveri,PK)、Lachancea thermotolerans(Lt)发酵的同一批葡萄酒中TDN含量存在差异,PK降低了葡萄酒中TDN含量,而Lt则提高了其含量[92]。

另外,酶制剂的直接应用能够有针对性地提高C13-降异戊二烯衍生物含量,与非酿酒酵母中糖苷酶较高活性类似,Candida easanensis JK8 中的β-葡萄糖苷酶在有较强葡萄酒酿造环境耐受性的同时,能够显著增加β-大马士酮含量[93]。

4.2.3 陈酿工艺 C13-降异戊二烯衍生物种类和含量随着陈酿时间的延长在葡萄酒中发生复杂的变化,赋予葡萄酒更浓郁复杂的香气。糖基化类胡萝卜素代谢物可以通过水解重排产生更多的游离态C13-降异戊二烯衍生物,如TDN[39]和β-大马士酮[14]。葡萄酒新酒中,TDN 及葡萄螺烷含量很低,随着陈酿时间的延长,含量皆呈现上升趋势[92]。但在一些情况中,陈酿早期C13-降异戊二烯衍生物含量提高,随着时间的延长含量降低[94]。Davide 等[95]的研究中,葡萄酒中β-大马士酮和3-氧代-α-紫罗兰酮含量在陈酿早期上升,但在陈酿168 h后低于初始值。

在陈酿过程中,葡萄酒的陈酿容器、工艺、储藏时间、位置和储藏环境都会影响C13-降异戊二烯衍生物含量。瓶盖会吸收一部分游离态C13-降异戊二烯衍生物,在5 款瓶塞对TDN 吸收能力的比较中,发现软木塞对TDN表现出较强的亲和力,螺旋盖的吸收较弱,而玻璃塞有最弱的TDN 吸收效果,垂直放置和较低的温度能够促进瓶塞对TDN 的吸收[95-96]。另外,在一项关于氧气供应、陈酿时间对葡萄酒品质影响的研究中,发现β-大马士酮和β-紫罗兰酮含量受到氧气供应量的正面影响和陈酿时间的负面影响[95]。

综上可见,原料前处理、发酵工艺和陈酿工艺都会影响葡萄酒中C13-降异戊二烯衍生物含量,但影响因素很多,且对不同组分的影响是不同的,这些因素的影响也可能是综合的,目前关于酿酒工艺的影响机制尚不明了。

4.2.4 反应条件 葡萄酒中存在着复杂的反应,推断无论是发酵工艺还是陈酿工艺,它们对C13-降异戊二烯衍生物含量的影响都可能与反应条件的改变有关,pH、温度等条件的变化都会影响C13-降异戊二烯衍生物的积累。研究表明,50 ℃、75 ℃、100 ℃三种温度中,较高温度有利于TDN 的合成[10],虽然研究温度与实际生产中相差较大,但一定程度上反映了在葡萄酒中C13-降异戊二烯衍生物合成时温度可能的影响机制。发酵温度对葡萄酒挥发性物质影响的研究较少,但较早之前有文献报道,相对于15 ℃,30 ℃发酵增强了葡萄酒的颜色和‘黑加仑’香气[97]。最近的研究发现,17 ℃、21 ℃、25 ℃发酵温度之间进行比较,发酵温度的升高增加了葡萄酒中β-大马士酮、β-紫罗兰酮含量[98]。

除了温度的影响外,pH 也发挥着重要作用,较低pH值有利于TDN的生成。在‘雷司令’酒中设定不同的温度、pH 值、水解时间组合,发现低pH 值下产生的TDN 的浓度远高于之前商业瓶装的澳大利亚‘雷司令’酒中的最高浓度,而猕猴桃醇含量较低[10],证实在酸性条件下,葡萄酒中其他前体物可以转化为TDN。

在葡萄酒成熟过程中,氧气的影响对葡萄酒香气非常重要,氧气的接触会使TDN和葡萄螺烷的浓度提高[99]。一定程度上氧气量的增加对β-大马士酮和β-紫罗兰酮含量的提高有积极作用[95]。

5 总结及展望

总之,C13-降异戊二烯衍生物是葡萄及葡萄酒中重要的香气物质,在葡萄果实和葡萄酒中以类胡萝卜素为前体物,通过VvCCDs 酶促裂解产生或者酸介导的水解产生,生物合成相关基因的研究也取得一定进展,但对于不同类胡萝卜素组分对应生成C13-降异戊二烯衍生物的复杂生化途径仍缺乏明确的机制,尚需更多的研究,如追踪类胡萝卜素的转化,监测转录和蛋白水平的变化及其调控机制等,以阐明类胡萝卜素到C13-降异戊二烯衍生物的转化机制。

葡萄及葡萄酒中香气物质含量受到众多因素如气候条件和酿酒工艺的影响,通过栽培措施的调控可以改变葡萄和葡萄酒中C13-降异戊二烯衍生物含量,但目前关于这些因素产生影响的研究大多集中于C13-降异戊二烯衍生物含量和种类的变化上,未来的研究应给予影响与调控机制更多关注。此外,各影响因素之间存在复杂的相互作用,因此在未来的研究中可以严格地控制单一变量,分别进行单一与组合因素的研究,从而选出最优的措施,如最佳的光照与水分组合。

不同种类的C13-降异戊二烯衍生物之间以及与其他香气物质之间存在着密切的联系,例如TDN与葡萄螺烷可能具有相同的代谢途径[6],因此在探究各种因素的影响时只关注单一物质并进行调控,很难实现对果实和葡萄酒整体香气的优化,甚至可能导致香气失衡。在未来的研究中,应重点关注C13-降异戊二烯衍生物之间的转化和其他香气物质以及糖、酸等与品质相关物质的变化,阐明香气物质间的相互影响机制,从而为提高葡萄酒整体品质提供理论指导。

[1] VILANOVA M,GENISHEVA Z,BESCANSA L,MASA A,OLIVEIRA J M. Changes in free and bound fractions of aroma compounds of four Vitis vinifera cultivars at the last ripening stages[J].Phytochemistry,2012,74:196-205.

[2] LIN J,MASSONNET M,CANTU D.The genetic basis of grape and wine aroma[J].Horticulture Research,2019,6:81.

[3] 孟楠,刘斌,潘秋红.葡萄果实降异戊二烯类物质合成调控研究进展[J].园艺学报,2015,42(9):1673-1682.MENG Nan,LIU Bin,PAN Qiuhong. Research advance on biosynthesis and regulation of norisoprenoids in grape berry[J].Acta Horticulturae Sinica,2015,42(9):1673-1682.

[4] PINEAU B,BARBE J C,LEEUWEN C V,DUBOURDIEU D.Which impact for β-damascenone on red wines aroma[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry,2007,55(10): 4103-4108.

[5] 温可睿,黄敬寒,潘秋红,段长青,王军.葡萄香气物质及其影响因素的研究进展[J].果树学报,2012,29(3):454-460.WEN Kerui,HUANG Jinghan,PAN Qiuhong,DUAN Changqing,WANG Jun. Research progress of aromatic compounds and influencing factors in grapes[J]. Journal of Fruit Science,2012,29(3):454-460.

[6] MENDES-PINTO M M. Carotenoid breakdown products the norisoprenoids in wine aroma[J].Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics,2009,483(2):236-245.

[7] YUAN F,QIAN M C. Development of C13-norisoprenoids,carotenoids and other volatile compounds in Vitis vinifera L.cv.Pinot Noir grapes[J].Food Chemistry,2016,192:633-641.

[8] MENG N,YAN G L,ZHANG D,LI X Y,DUAN C Q,PAN Q H. Characterization of two Vitis vinifera carotenoid cleavage dioxygenases by heterologous expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae[J].Molecular Biology Reports,2019,46(1):6311-6323.

[9] LASHBROOKE J G,YOUNG P R,DOCKRALL S J,VASANTH K,VIVIER M A. Functional characterisation of three members of the Vitis vinifera L. carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase gene family[J].BMC Plant Biology,2013,13(1):156.

[10] GREBNEVA Y,BELLON J R,HERDERICH M J,RAUHUT D,STOLL M,HIXSON J L.Understanding yeast impact on 1,1,6-trimethyl-1,2-dihydronaphthalene formation in Riesling wine through a formation-pathway-informed hydrolytic assay[J].Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry,2019,67(49): 13487-13495.

[11] MENN N L,LEEUWEN C V,PICARD M,RIQUIER L,REVEL G D,MARCHAND S.Effect of vine water and nitrogen status,as well as temperature,on some aroma compounds of aged red Bordeaux wines[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry,2019,67(25):7098-7109.

[12] ALEM H,RIGOU P,SCHNEIDER R,OJEDA H,TORREGROSA L. Impact of agronomic practices on grape aroma composition: a review[J]. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture,2019,99(3):975-985.

[13] GUTIERREZ- GAMBOA G,GARDE- CERDAN T,RUBIOBRETON PEREZ-ÁLVAREZ E P. Seaweed foliar applications at two dosages to Tempranillo Blanco (Vitis vinifera L.) grapevines in two seasons: effects on grape and wine volatile composition[J].Food Research International,2020,130:108918.

[14] ASPROUDI A,FERRANDINO A,BONELLO F,VAUDANO E,POLLON M,PETROZZIELLO M. Key norisoprenoid compounds in wines from early-harvested grapes in view of climate change[J].Food Chemistry,2018,268:143-152.

[15] ZIEGLER M,GOK R,BECHTLOFF P,WINTERHALTER P,SCHMARR H G,FISCHER U. Impact of matrix variables and expertise of panelists on sensory thresholds of 1,1,6-trimethyl-1,2-dihydronaphthalene known as petrol off-flavor compound in Riesling wines[J]. Food Quality and Preference,2019,78:103735.

[16] GHASTE M,NARDUZZI L,CARLIN S,VRHOVSEK U,SHULAEV V,MATTIVI F. Chemical composition of volatile aroma metabolites and their glycosylated precursors that can uniquely differentiate individual grape cultivars[J]. Food Chemistry,2015,188:309-319.

[17] SACKS G L,GATES M J,FERRY F X,LAVIN E H,KURTZ A J,ACREE T E. Sensory threshold of 1,1,6-Trimethyl-1,2-dihydronaphthalene (TDN) and concentrations in young Riesling and non-Riesling wines[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry,2012,60(12):2998-3004.

[18] SONG J,SMART R,WANG H,DAMBERGS B,SPARROW A,QIAN M C.Effect of grape bunch sunlight exposure and UV radiation on phenolics and volatile composition of Vitis vinifera L.cv.Pinot Noir wine[J].Food Chemistry,2015,173:424-431.

[19] ROCCO L,ANNA C,SAMANTHA S,KEMP B,KERSLAKE F.A review on the aroma composition of Vitis vinifera L. Pinot noir wines: origins and influencing factors[J]. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition,2020. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2020.1762535.

[20] FERRERO-DEL-TESO S,ARIAS I,ESCUDERO A,FERREIRA V,FERNANDEZ-ZURBANO P,SAENZ-NAVAJAS M P. Effect of grape maturity on wine sensory and chemical features: the case of Moristel wines[J]. LWT-Food Science and Technology,2020,118:108848.

[21] LUO J Q,BROTCHIE J,PANG M,MARRIOTT P J,HOWELL K,ZHANG P Z.Free terpene evolution during the berry maturation of five Vitis vinifera L. cultivars[J]. Food Chemistry,2019,299:125101.

[22] BLACK C A,PARKER M,SIEBERT T E,FRANCIS I L.Terpenoids and their role in wine flavour: recent advances[J].Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research,2015,21(S1): 582-600.

[23] SCHUTTLER A,FRIEDEL M,JUNG R,RAUHUT D,DARRIET P. Characterizing aromatic typicality of Riesling wines:merging volatile compositional and sensory aspects[J].Food Research International,2015,69:26-37.

[24] ZIEGLER M,WEGMANN-HERR P,SCHMARR H G,GOK R,WINTERHHALTER P,FISCHER U. Impact of rootstock,clonal selection,and berry size of Vitis vinifera sp. Riesling on the formation of TDN,vitispiranes,and other volatile compounds[J].Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry,2020,68(12):3834-3849.

[25] JANUSZ A,CAPONE D L,PUGLISI C J,PERKINS M V,ELSEY G M,SEFTON M A.(E)-1-(2,3,6-Trimethylphenyl)buta-1,3-diene: a potent grape-derived odorant in wine[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry,2004,51(26):7759-7763.

[26] ESCUDERO A,CAMPO E,FARIÑA L,CACHO J,FERREIRA V.Analytical characterization of the aroma of five premium red wines:Insights into the role of odor families and the concept of fruitiness of wines[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry,2007,55(11):4501-4510.

[27] MATHIEU S,TERRIER N,PROCUREUR J,BIGEY F,GUNATA Z.A carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase from Vitis vinifera L.:functional characterization and expression during grape berry development in relation to 13-norisoprenoid accumulation[J].Journal of Experimental Botany,2005,56(420):2721-2731.

[28] ASPROUDI A,PETROZZIELLO M,CAVALLETTO S,GUIDONI S. Grape aroma precursors in cv. Nebbiolo as affected by vine microclimate[J].Food Chemistry,2016,211:947-956.

[29] ZHANG P Z,FUENTES S,SIEBERT T,KRSTIC M,HERDERICH M,BARLOW E W R,HOWELL K. Terpene evolution during the development of Vitis vinifera L. cv. Shiraz grapes[J].Food Chemistry,2016,204:463-474.

[30] SUKLJE K,CARLIN S,STANSTRUP J,ANTALICK J,BLACKMAN J W,MEEKS C,DELOIRE A,SCHMIDTKE L M,VRHOVSEK U. Unravelling wine volatile evolution during Shiraz grape ripening by untargeted HS-SPME-GC×GC-TOFMS[J].Food Chemistry,2019,277:753-769.

[31] GAO X T,LI H Q,WANG Y,PENG W T,CHEN W,CAI X D,LI S D,HE F,DUAN C Q,WANG J. Influence of the harvest date on berry compositions and wine profiles of Vitis vinifera L.‘Cabernet Sauvignon’under a semiarid continental climate over two consecutive years[J]. Food Chemistry,2019,292: 237-246.

[32] TALAVERANO I,UBEDA C,CACERES-MELLA A,VALDES M E,PASTENES C,PENA-NEIRA A. Water stress and ripeness effects on the volatile composition of Cabernet Sauvignon wines[J]. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture,2018,98(3):1140-1152.

[33] LENG X,WANG P,WANG C,ZHU X D,LI X P,LI H Y,MU Q,LI A,LIU Z J,FANG J G. Genome-wide identification and characterization of genes involved in carotenoid metabolic in three stages of grapevine fruit development[J]. Scientific Reports,2017,7(1):4216.

[34] CHEN W K,YU K J,LIU B,LAN Y B,SUN R Z,LI Q,HE F,PAN Q H,DUAN C Q,WANG J.Comparison of transcriptional expression patterns of carotenoid metabolism in‘Cabernet Sauvignon’grapes from two regions with distinct climate[J]. Journal of Plant Physiology,2017,213:75-86.

[35] MENG N,WEI Y,GAO Y,YU K J,CHENG J,LI X,DUAN C Q,PAN Q H. Characterization of transcriptional expression and regulation of carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase 4b in grapes[J].Frontiers in Plant Science,2020,11:483.

[36] SEFTON M A,SKOUROUMOUNIS G K,ELSEY G M,TAYLOR D K. Occurrence,sensory impact,formation,and fate of damascenone in grapes,wines,and other foods and beverages[J].Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry,2011,59(18):9717-9746.

[37] XIE S,LEI Y J,WANG Y J,WANG X Q,REN R H,ZHANG Z W. Influence of continental climates on the volatile profile of Cabernet Sauvignon grapes from five Chinese viticulture regions[J].Plant Growth Regulation,2019,87:83-92.

[38] ARIAS-PEREZ I,FERRERO-DEL-TESO S,SAENZ-NAVAJAS M P,FERNANDEZ-ZURBANO P,LACAU B,ASTRAIN J,BARON C,FERREIRA V,ESCUDERO A.Some clues about the changes in wine aroma composition associated to the maturation of“neutral”grapes[J].Food Chemistry,2020,320:126610.

[39] ASPROUDI A,PETROZZIELLO M,CAVALLETTO S,FERRANDINO A,MANIA E,GUIDONI S.Bunch microclimate affects carotenoids evolution in cv. Nebbiolo (Vitis vinifera L.)[J].Applied Science-Basel,2020,10(11):3846.

[40] VILANOVA M,GENISHEVA Z,TUBIO M,ALVAREZ K,LISSARRAGUE J R,OLIVEIRA J M.Effect of vertical shoot-positioned,Scott-Henry,Geneva double-curtain,Arch-Cane,and parral training systems on the volatile composition of Albariño wines[J].Molecules,2017,22(9):1500.

[41] BAHENA-GARRIDO S M,OHAMA T,SUEHIRO Y,HATA Y,ISOGAI A,IWASHITA K,GOTO-YAMAMOTO N,KOYAMA K. The potential aroma and flavor compounds in Vitis sp.cv.Koshu and V.vinifera L.cv.Chardonnay under different environmental conditions[J].Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture,2019,99(4):1926-1937.

[42] LIU D,GAO Y,LI X X,LI Z,PAN Q H.Attenuated UV radiation alters volatile profile in Cabernet Sauvignon grapes under field conditions[J].Molecules,2015,20(9):16946-16969.

[43] DRAPPIER J,THIBON C,RABOT A,GENY-DENIS L. Relationship between wine composition and temperature: impact on Bordeauxwinetypicityinthecontextofglobalwarming:review[J].Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition,2019,59(1):14-30.

[44] FALCÃO L D,DE REVEL G,PERELLO M C,MOUTSIOU A,ZANUS M C, BORDIGNON-LUIZ M T. Effect of canopy microclimate,season and region on Sauvignon Blanc grape composition and wine quality[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry,2009,55(9):3605-3612.

[45] SUKLJE K,CARLIN S,ANTALICK G,BLACKMAN J W,DELOIRE A,VRHOVSEK U,SCHMIDTKE L M. Regional discrimination of Australian Shiraz wine volatome by GC×GCTOF-MS[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry,2019,67(36):10273-10284.

[46] XU X Q,LIU B,ZHU B Q,LAN Y B,GAO Y,WANG D,REEVES J R,DUAN C Q. Differences in volatile profiles of Cabernet Sauvignon grapes grown in two distinct regions of China and their responses to weather conditions[J]. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry,2015,89:123-133.

[47] MARTIN D,GROSE C,FEDRIZZI B,STUART L,ALBRIGHT A,MCLACHLAN A. Grape cluster microclimate influences the aroma composition of Sauvignon Blanc wine[J].Food Chemistry,2016,210:640-647.

[48] SONG J,SHELLIE K C,WANG H,QIAN M C. Influence of deficit irrigation and kaolin particle film on grape composition and volatile compounds in Merlot grape (Vitis vinifera L.)[J].Food Chemistry,2012,134(2):841-850.

[49] BINDON K A,DRY P R,LOVEYS B R. Influence of plant water status on the production of C13-norisoprenoid precursors in Vitis vinifera L. cv. Cabernet Sauvignon grape berries[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry,2007,55(11):4493-4500.

[50] JOUBERT C,YOUNG P R,EYEGHE-BICKONG H A,VIVIER M A. Field-grown grapevine berries use carotenoids and the associated xanthophyll cycles to acclimate to UV exposure differentially in high and low light (shade) conditions[J]. Frontiers of Plant Science,2016,7:786.

[51] FENG H,YUAN F,SKINKIS P A,QIAN M C. Influence of cluster zone leaf removal on Pinot noir grape chemical and volatile composition[J].Food Chemistry,2015,173:414-423.

[52] YOUNG P R,EYEGHE-BICKONG H A,PLESSIS K D,ALEXANDERSSON E,JACOBSON D A,COETZEE Z,DELOIRE A,VIVIER M A. Grapevine plasticity in response to an altered microclimate: Sauvignon Blanc modulates specific metabolites in response to increased berry exposure[J].Plant Physiology,2016,170(3):1235-1254.

[53] WANG Y,HE L,PAN Q H,DUAN C Q,WANG J. Effects of basal defoliation on wine aromas:a meta-analysis[J].Molecules,2018,23(4):779-797.

[54] BUBOLA M,RUSJAN D,LUKIĆ I. Crop level vs. leaf removal: Effects on Istrian Malvasia wine aroma and phenolic acids composition[J].Food Chemistry,2020,312:126046.

[55] HE L,XU X,WANG Y,CHEN W K,SUN R Z,CHEN G,LIU B,CHEN W,DUAN C Q,WANG J,PAN Q H. Modulation of volatile compound metabolome and transcriptome in grape berries exposed to sunlight under dry-hot climate[J].BMC Plant Biology,2020,20:59.

[56] GUIDONI S,OGGERO G,CRAVERO S,RABINO M,CRAVERO M,BALSARI P. Manual and mechanical leaf removal in the bunch zone (Vitis vinifera L. cv. Barbera): effects on berry composition,health,yield and wine quality,in a warm temperate area[J].Oeno One,2016,42(1):49.

[57] WANG Y,HE Y N,HE L,HE F,CHEN W,DUAN C Q,WANG J. Changes in global aroma profiles of Cabernet Sauvignon in response to cluster thinning[J]. Food Research International,2019,122:56-65.

[58] ZOECKLEIN B W,WOLF T K,PELANNE L,MILLER M K,BIRKENMAIER S S.Effect of vertical shoot-positioned,smart-Dyson,and Geneva double-curtain training systems on Viognier grape and wine composition[J]. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture,2008,59(1):11-21.

[59] GAO Y,LI X X,HAN M M,YANG X F,LI Z,WANG J,PAN Q H. Rain-shelter cultivation modifies carbon allocation in the polyphenolic and volatile metabolism of Vitis vinifera L. Chardonnay grapes[J].Plos One,2016,11(5):e0156117.

[60] HE Y N,NING P F,YUE T X,ZAHNG Z W. Volatile profiles of Cabernet Gernischet wine under rain-shelter cultivation and open-field cultivation using solid-phase micro-extraction-gas chromatography/mass spectrometry[J]. International Journal of Food Properties,2017,20(10):2181-2196.

[61] 迟明,刘美迎,宁鹏飞,张振文.避雨栽培对酿酒葡萄果实品质和香气物质的影响[J].食品科学,2016,37(7):27-32.CHI Ming,LIU Meiying,NING Pengfei,ZHANG Zhenwen.Effect of rain-shelter cultivation on fruit quality and aroma components in wine grape(Vitis vinifera L.)[J].Food Science,2016,37(7):27-32.

[62] XI Z M,TAO Y S,ZHANG L,LI H. Impact of cover crops in vineyard on the aroma compounds of Vitis vinifera L.cv.Cabernet Sauvignon wine[J].Food Chemistry,2011,127(2):516-522.

[63] 李越,姚冠榕,陈武,陈新军,王军,潘秋红.疏穗处理对‘赤霞珠’葡萄果实糖、酸及异戊二烯类香气物质积累的影响[J].果树学报,2018,35(2):185-194.LI Yue,YAO Guanrong,CHEN Wu,CHEN Xinjun,WANG Jun,PAN Qiuhong. Effect of cluster thinning on sugar/acidity and the accumulation of isoprene-derivated volatiles in‘Cabernet Sauvignon’grape berries[J].Journal of Fruit Science,2018,35(2):185-194.

[64] RUTAN T E,HERBST-JOHNSTONE M,KILMARTIN P A.Effect of cluster thinning Vitis vinifera cv.Pinot Noir on wine volatile and phenolic composition[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry,2018,66(38):10053-10066.

[65] WANG Y,CHEN W K,GAO X T,HE L,YANG X F,HE F,DUAN C Q,WANG J. Rootstock-mediated effects on Cabernet Sauvignon performance: vine growth,berry ripening,flavonoids,and aromatic profiles[J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences,2019,20(2):401.

[66] GAO X T,WU M H,SUN D,LI H Q,CHEN W K,YANG H Y,LIU F Q,WANG Q C,WANG Y Y,WANG J,HE F. Effects of gibberellic acid(GA3)application before anthesis on rachis elongation and berry quality and aroma and flavour compounds in Vitis vinifera L.‘Cabernet Franc’and‘Cabernet Sauvignon’grapes[J]. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture,2020,100(9):3729-3740.

[67] HE L,REN Z Y,WANG Y,FU Y Q,LI Y,MENG N,PAN Q H.Variation of growth-to-ripening time interval induced by abscisic acid and synthetic auxin affecting transcriptome and flavor compounds in Cabernet Sauvignon grape berry[J].Plants,2020,9(5):630.

[68] WANG W,MUHAMMAD K U R,FENG J,TAO J M. RNAseq based transcriptomic analysis of CPPU treated grape berries and emission of volatile compounds[J].Journal of Plant Physiology,2017,218:155-166.

[69] GUTIERREZ-GAMBOA G,PEREZ-ÁLVAREZ E P,RUBIOBRETON P,GARDE-CERDAN T. Changes on grape volatile composition through elicitation with methyl jasmonate,chitosan,and a yeast extract in Tempranillo (Vitis vinifera L.) grapevines[J].Scientia Horticulturae,2019,244:257-262.

[70] GOMEZ-PLAZA E,MESTRE-ORTUNO L,RUIZ-GARCIA Y,FERNANDEZ-FERNANDEZ J I,LOPEZ-ROCA J M.Effect of benzothiadiazole and methyl jasmonate on the volatile compound composition of Vitis vinifera L. Monastrell grapes and wines[J].American Journal of Enology and Viticulture,2012,63(3):394-401.

[71] D'ONOFRIO C,MATARESE F,CUZZOLA A. Effect of methyl jasmonate on the aroma of Sangiovese grapes and wines[J].Food Chemistry,2018,242:352-361.

[72] LOSCOS N,HERNANDEZ-ORTE P,CACHO J,FERREIRA V. Comparison of the suitability of different hydrolytic strategies to predict aroma potential of different grape varieties[J].Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry,2009,57(6): 2468-2480.

[73] GOEK R,BECHTLOFF P,ZIEGLER M,SCHMARR H G,FISCHER U,WENTERHALTER P. Synthesis of deuterium-labeled 1,1,6-trimethyl-1,2-dihydronaphthalene(TDN)and quantitative determination of TDN and isomeric vitispiranes in Riesling wines by a stable-isotope-dilution assay[J].Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry,2019,67(22):6414-6422.

[74] WONG D C J,GUTIERREZ R L,DIMOPOULOS N,GAMBETTA G A,CASTELLARIN S D. Combined physiological,transcriptome,and cis-regulatory element analyses indicate that key aspects of ripening,metabolism,and transcriptional program in grapes(Vitis vinifera L.)are differentially modulated accordingly to fruit size[J].BMC Genomics,2016,17:416.

[75] FRIEDEL M,SORRENTINO V,BLANK M,SCHUTTLER A.Influence of berry diameter and colour on some determinants of wine composition of Vitis vinifera L. cv. Riesling[J]. Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research,2016,22(2):215-225.

[76] XIE S,TANG Y H,WANG P,SONG C Z,DUAN B B,ZHANG Z W,MENG J F. Influence of natural variation in berry size on the volatile profiles of Vitis vinifera L. cv. Merlot and Cabernet Gernischt grapes[J].Plos One,2018,13(9):e0201374.

[77] 吴明辉,陈为凯,何非,王羽西,刘鑫,杨哲,朱燕溶,石英,段长青,王军.赤霞珠葡萄浆果质量对酿酒品质的影响[J].中外葡萄与葡萄酒,2017(1):9-17.WU Minghui,CHEN Weikai,HE Fei,WANG Yuxi,LIU Xin,YANG Zhe,ZHU Yanrong,SHI Ying,DUAN Changqing,WANG Jun. Influences of the berry weight on wine-making qualitative characteristics of Cabernet Sauvignon[J]. Sino-Overseas Grapevine&Wine,2017(1):9-17.

[78] LAN Y B,XIANG X F,QIAN X,WANG J M,LING M Q,ZHU B Q,LIU T,SUN L B,SHI Y,REYNOLDS A G,DUAN C Q. Characterization and differentiation of key odor-active compounds of‘Beibinghong’ice wine and dry wine by gas chromatography-olfactometry and aroma reconstitution[J]. Food Chemistry,2019,287:186-196.

[79] SUKLJE K,ZHANG X,ANTALICK G,CLARK A C,DELOIRE A,SCHMIDTKE L M. Berry shriveling significantly alters Shiraz (Vitis vinifera L.) grape and wine chemical composition[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry,2016,64(4):870-880.

[80] BELLINCONTRO A,MATARESE F,D’ONOFRIO C,ACCORDINI D,TOSI E,MENCARELLI F. Management of postharvest grape withering to optimise the aroma of the final wine:a case study on amarone[J]. Food Chemistry,2016,213: 378-387.

[81] LAN Y B,QIAN X,YANG Z J,XIANG X F,YANG W Y,LIU T,ZHU B Q,PAN Q H,DUAN C Q. Striking changes in volatile profiles at sub-zero temperatures during over-ripening of‘Beibinghong’grapes in Northeastern China[J]. Food Chemistry,2016,212:172-182.

[82] OUELLET E,PEDNEAULT K. Impact of frozen storage on the free volatile compound profile of grape berries[J]. American Journal of Enology&Viticulture,2016,67(2):239-244.

[83] GEFFROY O,LOPEZ R,FEILHES C,VIOLLEAU F,KLEIBER D,FAVAREL J L,FERREIRA V.Modulating analytical characteristics of thermovinified Carignan musts and the volatile composition of the resulting wines through the heating temperature[J].Food Chemistry,2018,257:7-14.

[84] GONZALEZ-ARENZANA L,SANTAMARIA R,ESCRIBANO-VIANA R,PORTU J,GARIJO P,LOPEZ-ALFARO I,LOPEZ R,SANTAMARIA P,GUTIERREZ A R. Influence of the carbonic maceration winemaking method on the physicochemical,colour,aromatic and microbiological features of tempranillo red wines[J].Food Chemistry,2020,319:126569.

[85] ZHANG Y S,DU G,GA Y T,WANG L W,MENG D,LI B J,BRENNAN C,WANG M Y,ZHAO H,WANG S Y. The effect of carbonic maceration during winemaking on the color,aroma and sensory properties of‘Muscat Hamburg’wine[J]. Molecules,2019,24(17):3120.

[86] CAI J,ZHU B Q,WANG Y H,LU L,LAN Y B,REEVES M J,DUAN C Q.Influence of pre-fermentation cold maceration treatment on aroma compounds of Cabernet Sauvignon wines fermented in different industrial scale fermenters[J]. Food Chemistry,2014,154:217-229.

[87] YAN G L,DUAN L L,LIU P T,DUAN C Q. Transcriptional comparison investigating the influence of the addition of unsaturated fatty acids on aroma compounds during alcoholic fermentation[J].Frontiers in Microbiology,2019,10:1115.

[88] LIU P T,DUAN C Q,YAN G L.Comparing the effects of different unsaturated fatty acids on fermentation performance of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and aroma compounds during red wine fermentation[J].Molecules,2019,24(3):538.

[89] HU K,QIN Y,TAO Y S,ZHU X L,PENG C T,ULLAH N.Potential of glycosidase from non- Saccharomyces isolates for enhancement of wine aroma[J]. Journal of Food Science,2016,81(4):935-943.

[90] 尤雅,段长青,燕国梁.扁平云假丝酵母与酿酒酵母混合发酵对葡萄酒乙醇含量及香气的影响[J].食品科学,2018,39(20):146-154.YOU Ya,DUAN Changqing,YAN Guoliang. Effects of mixed fermentation of Candida humilis and Saccharomyces cerevisiae on ethanol content and aroma of wine[J].Food Science,2018,39(20):146-154.

[91] 申静云,刘沛通,段长青,燕国梁.不同有孢汉逊酵母与酿酒酵母混合发酵对威代尔冰葡萄酒香气的影响[J].食品与发酵工业,2017,43(10):16-23.SHEN Jingyun,LIU Peitong,DUAN Changqing,YAN Guoliang.Effects of mixed fermentation by different Hanseniaspora genus yeasts and Saccharomyces cerevisiae on the aroma compounds in Vidal ice wine[J].Food and Fermentation Industries,2017,43(10):16-23.

[92] OLIVEIRA I,FERREIRA V. Modulating fermentative,varietal and aging aromas of wine using non-Saccharomyces yeasts in a sequential inoculation approach[J]. Microorganisms,2019,7(6):164.

[93] THONGEKKAEW J,FUJII T,MASAKI K,KOYAMA K.Evaluation of Candida easanensis JK8 β-glucosidase with potentially hydrolyse non-volatile glycosides of wine aroma precursors[J].Natural Product Research,2018,33(24):3563-3567.

[94] LIU D,XING R R,LI Z,YANG D M,PAN Q H. Evolution of volatile compounds,aroma attributes,and sensory perception in bottle-aged red wines and their correlation[J]. European Food Research and Technology,2016,241(11):1937-1948.

[95] DAVIDE S,MAURIZIO U. Norisoprenoids,sesquiterpenes and terpenoids content of valpolicella wines during aging:investigating aroma potential in relationship to evolution of tobacco and balsamic aroma in aged wine[J]. Frontiers in Chemistry,2018,6:66.

[96] TARASOV A,GIULIANI N,DOBRYDNEV A,MULLER N,VOLOVENKO Y,RAUHUT D,JUNG R.Absorption of 1,1,6-trimethyl-1,2-dihydronaphthalene (TDN) from wine by bottle closures[J].European Food Research and Technology,2019,245(11):2343-2351.

[97] REYNOLDS A,CLIFF M,GIRARD B,KOPP T G. Influence of fermentation temperature on composition and sensory properties of Semillon and Shiraz wine[J].American Journal of Enology and Viticulture,2001,52(3):235-240.

[98] IZQUIERDO- CANAS P M,VINAS M A G,MENA- MORALES A,NAVARRO J P,GARCIA-ROMERO E,MARCHANTE-CUEVAS L,GOMEZ-ALONSO S,SANCHEZ-PALOMO E. Effect of fermentation temperature on volatile compounds of Petit Verdot red wines from the Spanish region of La Mancha (central-southeastern Spain)[J]. European Food Research and Technology,2020,246(6):1153-1165.

[99] TARKO T,DUDA-CHODAK A,SROKA P,SIUTA M.The impact of oxygen at various stages of vinification on the chemical composition and the antioxidant and sensory properties of white and red wines[J]. International Journal of Food Science,2020,3:7902974.